Chapter 10

Recommendations

The widely held position that circuses, and sometimes zoos, necessarily cause suffering to animals because of their nature has not been found to be the case. In fact it has been argued that the possible positive aspects of what zoos and circuses could do for the animals under their care, and for humans perception of animals, outweighs the negative aspects of possible suffering of the animals in circuses and zoos.

However, there is evidence of distress in the animals in circuses and zoos, and in almost every other husbandry system. The question therefore is how must zoos and circuses be changed to reduce this distress and eventually to be able to design and manage animals systems so, as a rule, there is no evidence for prolonged suffering of the animals in them?

As a result of examining all the various arguments and the empirical data I have collected, it is my opinion that the efforts and money of animal welfare organisations should not go into trying to ban circuses and zoos. Instead they should put their efforts and money into reducing animals suffering, by research on these improvements and learning more about the behavioural and other needs of the different species, individuals, their cognition, and the education of humans to further respect and understand animals.

It is possible for circuses and zoos, as for any other animal management system, to achieve the aims outlined in the previous chapter. For circuses it may be, in some respects, more difficult because, for example, animals are transported around and therefore appropriate housing must be reconstructed quickly at each location. On the other hand, it may be easier in other respects to fulfil certain psychological needs than some other husbandry systems, such as zoos. This is because circuses by their nature specialise in handling and educating animals, and are primarily concemed with the individual.

I have argued that there are ways in which inappropriate environments which interfere with the animals rights and are likely to cause prolonged suffering can be quickly assessed. The criteria for doing this are outlined in Figures 68 and 73. It will not be possible to fulfil all these criteria immediately, nor will it be desirable for certain individual animals (for example, an elephant who has lived on her own for many years might find it traumatic to be thrust into a group) but in general they are the goals we should work towards in all our animal husbandry systems, particularly for the next generation of animals.

There are also ways in which we can assess if the environment is inappropriate for the individual: whether or not it is suffering or distressed. This can be done by assessing:

Inevitably there are grey areas in making these assessments, and in some cases more knowledge is required. For example, we have little information on normal time budgets and the amounts of aggression and affiliative behaviour, or behaviour often related to frustration and conflict for some species in unrestricted environments, so it is difficult in some cases to make judgements. Nevertheless, we do have enough information to make some assessments of suffering and cruelty. It is important, however, that skilled personnel implement these criteria. This requires detailed knowledge of practical stockmanship, ethology and some basic veterinary understanding.

The next question is, having assessed that there are problems in relation to these criteria for certain animals, in what respects do we change the environment to try and reduce or eradicate them?

The most important points here are:

Although there is not a great deal of information on many of these aspects, these are not vague concepts, but important criteria that must not be ignored if we are going to progress in our considerations of ethically acceptable environments for animals. It is the duty of those involved in animal husbandry to use all existing knowledge, and help to finance further research. Inevitably, this approach requires a consideration of individual cases. Here we can give some more detailed guidelines that might be appropriate for the most common circus species.

The physical environment

It is not ethologically sound to keep the elephants shackled for prolonged periods. Quickly constructed safe enclosures can be made using electric fences and the elephants should be allowed access to these for the majority of each 24 hours. They should also be taken out, allowed to roam about at will and on walks, parades, to the sea, river, beach or woodlands whenever and wherever possible. They must be properly educated so that this can be achieved without undue risk.

When in their living quarters the elephants should have access for the great majority of the time to high-fibre food, and preferably objects to manipulate, leaves to eat and so on. They should have plenty of bedding, and space to lie in (at least twice their own body size). Lying on bare concrete or wooden slats is unacceptable.Shackling should gradually be phased out, although it is advisable to train the elephants so that they can be shackled if essential. If it is not possible for certain managers to keep elephants safely without shackling them for prolonged periods, then they should not be kept.

The elephants should be kept in social groups, preferably family matriarchal groups including animals of different ages. If an elephant has always been alone, then it may well be that she is socially inept and would find close company distressing. Thus for her lifetime it may be suitable for her to remain alone, although she should have the opportunity to breed. This does not argue for keeping young elephants isolated in the future.

Each elephant (particularly the Indian elephants) should breed at least once in their lifetime in order to ensure the next generation and also to allow the existing animals to have and bring up young.

The elephants should be given training or education sessions daily so that they are learning new and different things and having to think. They should also be exposed to as many different situations as possible so that the risk of them becoming frightened and panicking is reduced. The handling and training of the elephants is particularly important and requires great dedication and skill, but the rewards in terms of the possible relationships between humans and elephants are very great.

The elephants might well benefit from helping around the circus moving heavy objects and so on, and the circus could certainly benefit from such activities. Elephants can be trained to perform certain tasks to make life easier for themselves and their human associates. For example, they can be taught to urinate and defaecate in certain places or even in a bucket or wheelbarrow; they can help to erect their own tents, to load the Big Top and so on.

The elephants should be taught to do appropriate acts to display their unique abilities, for example the manipulative ability of their trunk, their strength, the love of playing with objects and each other, and their great cognitive abilities and willingness to work. Their apparent fondness for each other and their handlers and trainers can also be shown.

Carnivores with particular reference to the big cats

The physical environment

Confining the cats to beast wagons or cages indoors for all or the majority of their time is not acceptable. The environment is dull, confined and restrictive. Even though circus animals (unlike zoo animals) leave the wagons or cages for some time each day for training or performance sessions, this is insufficient to allow them to perform all their behaviours. It is important that the conditions are improved not only when the circuses are on the road, but also in the winter quarters or on breeding and training farms.

All the cats and carnivores should have access to exercise yards or pens outside (unless the animals are sick and it would be bad for their physical health), for the majority of each day. Cages that allow the animals to leap, chase, bound, climb and perform other athletic activities in their species repertoires are required. In addition, these cages must be quick and easily constructed and taken down, and they must be safe for both the animals and the humans. This is not impossible to achieve; exercise ring cages can be constructed in the compounds with tunnel access for the different cats, or mesh cages constructed adjacent to the beast wagons which can then act as large extensions of their living areas.

There must be a greater provision of cage furniture in the beast wagons, particularly for the climbing cats. Shelves, climbing bars and logs which allow the cats to use the third dimension are essential. In addition, objects to manipulate, chew and play with should be provided for all. Natural vegetation, because it is aesthetically more pleasing, and possibly something that the animals might find easier to relate to, and is replaceable, could be used more widely. For example, tree branches with leaves can often be purchased on arrival at the new site.

Details such as the direction to which the wagon points, and thus the amount of sun the animals will receive; the outlook from the wagons; their positioning where there is sufficient interest and action around must also be considered, and may well make a large difference to the life of the animal.

The beast wagons should not be shut up at night when the weather is suitable. If they are shut up then the period of enclosure should be minimised, and certainly should not exceed eight hours. There is no excuse for the carnivore grooms not getting up early to allow their animals access to the light and the exercise yard. This is particularly necessary for animals such as the tiger, leopard and wolf who are often crepuscular or nocturnal in the wild.

The social structure of the groups in which the animals are kept should be considered carefully. For example, if social and non-social species are going to be in the same act and therefore kept together - such as lions and leopards - then suitable and different living accommodation should be provided. Again this is not necessarily impossible. For example, the smaller leopard can have an escape door through which only he can slink, into a private apartment, perhaps where he cannot be seen from outside.

All the carnivores should be allowed to breed at least once in their lives and to raise their own young. The groups should be constituted to allow this.

Handling and training

All the animals raised in the circus should be handled, preferably daily, and they should also have training sessions as well as give performances. The presenter/groom of the big cat acts usually has few, if any, tasks other than looking after his animals, and therefore s/he often has plenty of time to handle, play with, relate to and educate the carnivores. The training/educational programme should be appropriate to the species and the acts designed to show off the animals particular physical and behavioural abilities, whether it is climbing, balancing and leaping, or rolling around and playing - innovation in the acts is needed here.

Similar but species-appropriate criteria should be applied to all the other carnivores in circuses - bears, wolves, hyenas and domestic cats and dogs. Specific recommendations could be made for each species.

There were many domestic dogs in the circuses - some performers, some pets and some guard dogs - and it is worth emphasising that the same criteria must apply to them. There is no excuse for the dogs of any of these categories not being able to run free for at least part of the day, to be housed in trailers perhaps but with outside runs available all of the time, and to have social contact with conspecifics and with their human trainers or handlers. There is no reason, for example, that the dogs should bark persistently other than because the environment is in one way or another inappropriate. If this is what happens when they are kept outside, then all aspects of their environment must be reconsidered carefully, including their training which may not be up to standard. There is a widely held belief that good working dogs cannot be pets as well. That there are leading sheepdogs, circus performing dogs, retrievers, guide dogs for the blind and so on who are also pets (that are allowed to share the life of their human handlers to a great degree, and have profound emotional relationships with them) gives the lie to this statement.

If we are to work towards symbiotic relationships with animals, then this must also involve increasing the liberty of the animal so that he stays around and does what is required because he wants to not because he has no choice. There is no doubt that this can and does happen for dogs. In a circus where animal training is their profession, this should be seen to be the case. Where better to begin than with the dogs?

The physical environment

The tendency is to keep many of the exotic hoofed stock stalled and only to take them out for training and performance - this is unacceptable. In order for the animals to be able to perform more of the behaviour in their repertoire, it is necessary for them at least to be taken for walks, tethered outside, and allowed loose into enclosures daily. Again these enclosures can be constructed quickly using electric- fencing equipment, and could be attached to the stable tent so that the animals can go in or out as they wish (Figure 12, page 35).

Most of these animals are well adapted to eating a high-fibre diet, and normally spend a large portion of each day in the wild eating. They must have access to high- fibre food all the time. The best system is probably to feed hay ad libitum placed in racks or nets so that the animals have to work a little to obtain it. If water is on offer all the time, this is preferable but not essential as taking the animals to a central water butt twice a day can ensure that they are handled, and come into contact with others.

Rolling and scratching facilities

Another important feature that was universally neglected in the management of circus horses and other hoofed stock was the provision of suitable time and place for the animals to roll or scratch. These activities relieve skin irritation and may have other functions (e.g. leaving pheromones). In order to roll, horses and llamas in particular need an appropriate substrate (this can be grass, sawdust, straw etc.) and room to move, to pick their place and to get up afterwards. Horses, and probably llamas, can be taught to roll on command at suitable times, such as after exercise, in just the same way as they can be taught to defaecate and urinate in certain areas (see page 210). It is not difficult in a circus to provide the right time and place to encourage horses to roll, but I saw no evidence of this. Hediger [48] points out the importance of providing scratching posts for zebras and other animals. This can be done easily by knocking in a firm post in the enclosure, if there are no other suitable objects in the environment.

This is another important criteria for the hoofed stock. Generally, the animals were out of their tents for insufficient time each day (10 minutes - 2 hours) and during this time they did not have remotely the same amount of exercise that they would normally have in a feral or wild state or even at pasture or in a yard. Exercise will be increased if training, educating and taking the animals for walks and parades is increased. If the animals are loose in reasonable sized enclosures, which at some grounds is not difficult to arrange, they will exercise themselves more and this will also help.

Looseboxes are not necessarily better from the horses point of view than stalls since they often isolate the animal more from conspecific contact, and from the environment as a whole. The public and management often like the idea of hoofed stock, particularly horses, in individual stables with doors, and grating between the animals. Such systems are traditionally associated with what are usually considered quality animal breeding establishments. One must be cautious here if one is centrally involved with the animals welfare as opposed to the publics view of what is best. Graphics can often achieve much in this direction. They are sometimes used to good advantage in zoos but could be much more widely used in circuses.

These requirements are important. At the winter quarters there is sufficient space to be able to allow the hoofed animals out into fields. If there is difficulty catching them for training sessions, then the approach must not be one of confining the animal as a result, but rather one of self-questioning the training and catching techniques. It should be considered a pre-requisite of all circus hoofed animals (as for all other husbandry systems) that they have some period each year, say for 1-2 months when they are out in semi-liberty in large enclosures or fields. This is not difficult for most circuses to organise out of season as almost all have land available at their winter quarters.

Most hoofed animals are social species, but they have rather different types of social organisations. For example, some live in multi-male groups (e.g. cattle and bison), some in groups with one male (e.g. many of the equids). The majority of the species have home areas although they vary greatly in size from the quarter of a square mile of a bushbuck to the two home areas joined by a hundred-mile migration route of the Serengeti Wildebeest; or the several square mile areas in which eland live. Many other elements of their social organisations vary too.

Despite these differences it is possible, with thought, to cater for the individual animals and species needs in this regard even where there is only one of that species. It is, by definition, always better to have more than one individual of any social species. However this may not be always possible, and with care suitable relationships can be substituted by other species, including human beings. Thus close relationships and apparent companionship was provided by goats for ponies, cattle for eland, horses for zebras, and so on. The encouragement and development of these arrangements have to be managed with care. It is often best to start with young animals, who should be mother-raised to avoid the possibility of inappropriate sexual imprinting or other behavioural abnormalities.

Because of the most common management system at the moment which involves keeping many of the animals tied in stalls, the integration of old animals who have all their lives been prevented from free social contact with conspecifics is likely to be difficult and need particular care. This is not to say that it cannot be achieved, it is just a question of working out how it can. There is, however, no reason why more physically and socially appropriate environments should not be achieved for the next generation of hoofed stock; for example, feral stallions, which do not have harems, live in batchelor groups. With suitable social upbringing and careful introduction domestic stallions can be so kept [29]. The majority of horses in circuses are stallions. Efforts should be made to gradually allow them free social assocation together in social groups in enclosures for at least part of each day.

Breeding

The breeding of rare species, in particular, should be encouraged by careful formation and management of the groups. Breeding of other species, at least once during each animals lifetime, allows the individuals to exercise this aspect of their behaviours, and has the added advantage of keeping different genes in the populations [see 9 p. 46 on for simple discussion of the need for all individuals in small populations to breed).

The aims, however, of the circus are different although not necessarily inferior to those of most zoos whose main self-publicised aim is for the survival of the species. The emphasis in circuses is on the individual and its breeding must be considered in respect of the costs and benefits to the individual mother and the individual offspring. It may be that in certain cases, there will be no need or facilities for keeping and training more youngsters; in which case, temporary birth control may well have to be exercised. However irreversible surgery, particularly that with accompanying endocrinal and behavioural effects, such as castration or hysterectomy, is not recommended for either zoos or circuses. Mothers should be allowed and encouraged to raise their own young. In order to achieve this it is often important to be able to handle the mother safely as it is often easier to help the mother, but not be a substitute for her, even though, as is the case with so many captive-born females these days, she has had no experience of being mothered (she was herself hand raised) and therefore possibly less likely to be a good mother.

Only if natural mother rearing will cause the death of the young should they be taken away and hand reared. This is rarely the case if the mothers can be handled by experienced and skilled people. Inappropriate management often causes infant rejection by taking the infant away too soon or interfering too much with inexperienced mothers [authors animal behaviour consultancy results].

If infants are hand reared, although they may live closely with humans, they must also become integrated into their own species group and learn the appropriate species specific behaviour and organisation. If weaning away from the human rearers is then desirable eventually, this should be gradually and carefully done so that the animal does not show obvious signs of distress or behavioural restriction.

The training of all the animals should be taken more seriously, more regularly and preferably be more innovative, particularly with regard to educating the animals to perform activities which enhance humans respect for them by demonstrating their unique abilities and differences. Perhaps this could be done with suitable educational programmes for the animals, which could advance our understanding of the different species abilities. Time must be made available for daily training, handling and exercising of the animals. This can be done by:

There are many ways in which the further training of the animals for appropriate behaviour outside the ring could cut down labour and the time required for routine jobs. For example:

It is not impossible, or even difficult, to train horses or elephants to defaecate in specific places. This was done at three circuses to avoid them defaecating in the ring. An extension of that training to their living quarters is possible (particularly for stallions). Thus there could be specific places where the horses or elephants defaecate, or particular times so that the mucking out would become a quick and simple operation. One elephant had in fact already been trained in this way, and her handler simply presented a bucket or wheelbarrow to her at the appropriate times for her to muck or urinate into. An extension of this approach to other stock could be quite possible - dairy cattle, for example, can be trained not to defaecate in the milking parlour [P. Savage, Colin Godmans Farm, and other dairy farmers]. There is no reason to suppose other artiodactyls could not also learn such control.

b) Animals working

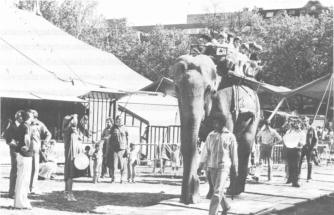

The animals could help with the work around the site. This could provide employment for them, is good advertising (since the majority of people like to see the animals doing something), and if it were sensibly organised could cut down human labour. For example, the elephants could help erect the tents, the horses and ponies and llama could pull small muck carts around, the dogs could help to herd appropriate hoofed stock, and so on. At one circus/zoo, horses pulled a tram around and elephants give rides at several circuses and one or two zoos (Figure 75). These are a few suggestions on the direction in which changes should be made.

Fig. 75. An elephant working by giving rides.

Although I was often impressed with the ring training of the animals, not often was the same degree of commitment and skill employed in the management of the stock outside the ring. This would be advantageous for the wellbeing of much of the stock and grooms, and is quite possible with the existing skills.

As with all animal management systems, good management involves constantly reassessing the system and the animals physical and mental health within it, as well as considering economic and other controls.

A useful concept here is one of sensible priorities. It is always possible to have different priorities in assessing animal management, but if one is centrally concerned with welfare (both physical and psychological) often the conventional priority list may have to be reviewed. This is true in circuses, as in any other husbandry (see for example Figure 27, page 58) which shows how very common behavioural signs of distress are in racehorses or horses used for teaching, managed to what are normally considered the highest standards. Clearly changes from established traditional practices are badly needed for horse management outside circuses as well as within them. Most of the management systems in zoos and circuses are tradition bound, and although the managers often seriously have the animals health and happiness as a central consideration, the priorities on how to achieve this were not always sensible. For example, there is a universal concern that all the animals should not be out in the rain, mist etc., even in the summer, despite the fact that summer rain showers are highly unlikely to cause physical illness to normally healthy adult mammals who are used to the European climate. The result was that animals were confined unnecessarily, and there was some coughing in the horses. The same type of problem is often encountered in zoos where until very recently the physical health of the animal, even at the risk of housing the animals in dull sterile conditions, has always taken priority [e.g. 53]. This has not been conducive to the animals psychological health and their ability to exercise many behaviours in their repertoire.

There are other odd practices which might, if nothing else, reduce the time spent by grooms doing repetitive, pointless tasks and thus liberate more time for them to spend with the animals, exercising, training and so on. Here are some examples:

The conventional stable management, on which British horse management manuals and much of the circus animal management is based, was designed to keep all the cavalry men (and these days working pupils) employed all day in the stables in order to keep them out of mischief [see 29]; so jobs were constantly invented for the grooms. All of what they do does not necessarily benefit the physical or psychological wellbeing of the animals. Of course, some practices are crucial, but others are not, and the good manager, particularly where labour is expensive and short, will understand this and decide on his/her priorities.

The health and happiness of the animals must always take priority however. If there is a conflict between these two, then the individual cases must be considered very carefully, and it must be understood that psychological health should not always play second fiddle to physical health, nor should the management become so intrusive and concerned that it becomes self-defeating and actually creates problem. This is often the case with modern horse and pet management. Good management is often synonymous with interfering and restricting the animal a great deal.

If the relationship between animals and humans is to develop along lines of symbiosis rather than exploitation of the animals, then it is important to have sensible priorities which examine and carefully balance the different pertinent factors. These priorities may well need reviewing as knowledge increases or conditions change.

Although some grooms may spend their entire lives in circuses, the majority of the grooms are casual employees who for various reasons want to join a circus for a time. Therefore not all the people looking after the animals are genuinely interested in them and committed. This does not matter as long as there is good supervision, and regular training, and the supervisor has sensible priorities.

If the public are going to be educated and have their awareness, interest and respect for the animals enhanced, the first impression must be one of professionalism, cleanliness and tidiness.

Most circuses are aware of this now. There are, however, problems that would daunt any but the committed - such as having to put the show on in a muddy field because the council has banned the circus on a better site. Such occurrences (I witnessed four), are not conducive to the animals welfare either, however hard the circus personnel work.

Around the time of the performance, the campsite is well ordered and tidy with the animal tents, mucked out and the stockpeople in their uniforms. For the rest of the day, however, when there may well be members of the public still wandering about, the tidiness standards may lapse. There are a few basic recommendations here which, if circuses are going to achieve they must attend to: for example, the stockpeople and public should have access to good clean toilets, and grooms should be provided with working overalls and good washing facilities.

Because the animals are on public view at performances twice a day, they are usually all regularly groomed and presented looking their best. It is easy (and often happens in horse stables and showing kennels) that the obsession with the cleanliness of the animals causes further restriction. For instance, horses or dogs may not be allowed out or let loose in a field because they will roll and get muddy which causes extra work for the grooms. This can be a problem for circuses too, but not an insurmountable one; for example, the use of rugs or washing on occasions for the hoofed stock, and electric groomers helps cut down grooming time so that the animals are not restricted in order to keep them clean.

Training circus grooms and trainers

It is recommended that a Circus Animal School should be started which would give apprentices a basic introduction to animal husbandry and particularly the theory and practice of animal handling and training. This would be the first of its kind, and it could attract students from many animal husbandry systems, including zoos, stables, kennels and so on. After a course, the students could be apprenticed to different circuses, and sit a qualification at the end, along the lines of a City and Guilds certificate. A similar system already exists for zookeepers, but the animal training school would, in addition to teaching normal husbandry requirements (such as nutrition, recognition of disease and prophylactic treatments), concentrate on handling and training.

The constant plea in circuses has been that the trainers who are often the proprietors, mechanics and/or general organisers as well, have insufficient time to do as much training as they would like. In order for training/educating of the animals to progress, and fulfil the necessary criteria, circuses should have a registered apprentice trainer/stockperson whose main job is to ensure that the animals are given sufficient individual training, exercise and so on. Such a person would be under the direction of the head trainer, and this would be an extra post, not someone doubling as a groom.

Fig. 76. A dolphin playing ball with some children voluntarily, not in a performance.

There are general recommendations here which have already been suggested in previous chapters. In the first place it is desirable that the acts should serve to enhance the specific characteristics of the species and individual and their abilities rather than their inabilities and weaknesses.

Secondly, it is not appropriate for the animals to be dressed up or displayed as if they were stupid or handicapped human beings.

Thirdly, it is desirable that whips, goads and other indications of potential negative reinforcement in the animal acts should be done away with or reduced substantially. The animals should show signs of pleasure in performing and no reluctance to enter the ring or fear of applause.

Displays which tend to enhance the courage and greatness of the presenter rather than the unique abilities and thus respect for animals should be discouraged; for example, attack-trained lions and tigers. An image of harmony and constructive cooperation between the animals and their presenters or trainers would be more admirable and display the potentially important aspect of the circus better.

It is desirable that the animal acts are innovative and aesthetically pleasing if they are to hold the attention of the audience and educate and entertain them.

There may be a place for demonstrating the tradition and history of circus, but it is unlikely that the possibly constructive aims of the circus in relation to animals will be enhanced by an emphasis on this.

Fig. 77. An appropriate act for the big cats, emphasising their ability to balance, their litheness, beauty and grace. Could they invent and develop acts for themselves, having learnt the technical building blocks? Do they have no aesthetic sense, no creativity, no ability for innovation?

The winter quarters of almost all the circuses need severe attention. The same criteria for keeping the animals on tour must be adhered to and they should be inspected regularly (inspectorate run by the Association of Circus Proprietors perhaps). The period in the winter quarters should be regarded as a holiday for the older trained animals that have been on tour - who should be allowed more freedom of movement, choice of environment and social contact during their period there. Any buildings should be adequately constructed and properly designed to maximise light, optimise ventilation, and heat conservation. It is possible to design buildings/tented accommodation which minimises labour and maximises the animals, choices and freedom.

Some have stated that they regard the circus as medieval (e.g. Desmond Morris in the Mail on Sunday 1989), implying that their attitude to animals is medieval, whatever this means. It is interesting to note that it was in this period that animals were considered to have rights and be responsible for their actions, they were even tried for criminal acts and sentenced [56].

Be this as it may, where do circuses go from here? Should they remain guardians of traditional entertainment if they manage to fulfil the conditions and improvements outlined here, or should they and could they progress further? And if so, where?

I believe, as I have pointed out, that circuses could play a very important and exciting role in our advancement and understanding of animals, and of animal cognition. Yet further, they could perhaps if they developed appropriately and thought seriously about these ideas be a pivot in making us think more about the possible aesthetic appreciation, creativity, and innovativeness that various individual animals may be capable of. Would it not be possible to work towards a new inter- species art form: multi-species opera/ballet/theatre? Is this just fancy-free lunacy - for the fairies?!

|

Any

non working links, comments or suggestions please contact the webmaster:

johneaston@diddly.co.uk |

|