Chapter 8

Arguments for zoos and circuses

The arguments usually given for zoos are:

1) The conservation and breeding of endangered species.

2) The carrying out of research as a result of having animals available.

3) Education of people, in zoology and particularly in environmental issues.

4) Provision of entertainment, and recreational facilities.

The majority of zoos are privately owned and have to survive financially on their own earnings; unlike farms where often the main stated aim is given as:

5) To run an efficient business which makes some money.

Zoos very rarely, if ever, mention this as one of their aims, although it clearly must be, even if only to cover costs.

Circuses have been slower to state their aims and put themselves across to the public as doing a social service. They usually therefore confine their stated aims to (4) and (5), and sometimes (3). However, on questioning, the main reason for the people who actually travel with the circus being there is:

6) A way of life.

There is no particular reason why, in theory at least, they should not try and fulfil (1) and (2) (breeding of endangered species, and research) and in fact one British circus has been more successful in breeding the endangered snow leopard than many zoos.

All of these seem, at face value, worthy aims

that few would quarrel with, even if they do consider that animals should have

equal consideration to humans and are beings of moral worth. The arguments arise

from:

a) the degree to which these aims are, or can in fact be fulfilled, and

b) the sacrifice of the individual animal to a low quality of life in order

to try and fulfil these aims - whether the end justifies the means.

There are other arguments that can be made for and against zoos and circuses which to my mind have not received the attention that they might.

We will consider each argument in turn, and examine the degree to which the aims can or are being fulfilled.

1) The breeding of endangered species

This argument is used often by zoos as their central raison detre. It is a relatively new idea which was pioneered by Gerald Durrell at the small Jersey Zoo about 15 years ago when there began to be more public concern about the extinction of species [118]. Since it is usually considered of particular importance by zoos themselves, it is the subject of a separate section (pages 172-173).

If zoos argue that they contribute to our knowledge of animals, then how much research have they done and are they doing, and what type of research is this?

The truth of it is that although in principle most zoos are in favour of having some research continuing on the behaviour of their animals, particularly now they have come under attack, very few zoos have financed research, even that which might lead to their own animals benefiting. Several American zoos have financed research personnel to go and work in the field in Africa and Asia, (e.g. The Smithsonian in Washington; The Bronx Zoo in New York), but very few have even one research person on their staff. Some zoos may encourage students and research personnel to come into the zoos and do some short-term work on their animals, but normally the money for this work has to be found from other sources.

Some of the financing is for high profile research, such as the tiger reproduction project at Minnesota Zoo, or the artificial insemination of giant pandas at London Zoo [9; 10]. This is research which comes under the auspices of Biological Research but is more biochemical/physiological. This research is often not involved with the whole animal even as a representative of a species, but rather one system. Although in the field particularly of veterinary science, such research can contribute to the welfare of animals in zoos, the use that is sometimes made of the zoo animals as laboratory specimens is not often known or exposed to the public.

This type of research is suspect for two reasons:

i) there is often no clear likelihood of the species or the individual benefitting from the pain and suffering caused;

ii) there are a host of immediate problems in terms of how to design the animals environments to cater for all aspects of their behaviour, and overcome behavioural abnormalities.

Zoos are becoming a little more conscious of the need to be seen to be financing research - and relevant research. There has recently been some advances in this areas [95; 97], but this remains an area of valid criticism [35].

Circuses have not usually considered research as an area where they could contribute. However, there are three areas where they are uniquely placed to do this, that is in research on:

i) differences between individuals: personality profiles, etc.

ii) training and human animal interactions; and most importantly

iii) in the field of animal cognition.

One British circus proprietor has mentioned as a priority that she would like to see more research being done on the behaviour of animals in circuses [119]. This may result in further financial contributions in this direction. Some European circuses have certainly encouraged research on their animals [120], but again there is little evidence that they have financed directly any research to date.

Lately, many zoos have been taking this issue seriously, and many have educational officers whose job it is to think up and publicise interesting and stimulating educational activities and displays for school children and families. Some zoos, for example the Bronx, New York, also have high tech teaching aids to try to put across environmental messages to adults.

This education almost exclusively concentrates on environmental issues, such as the destruction of the forests, loss of habitats worldwide, climatic changes, and species information. The exhibits in the collection are simply representatives of a species whose habitat and habits are described briefly. There is in this way a heavy emphasis on science, although some rely on imaginative imagery and originality in putting across conservation messages and general zoological information.

Occasionally the animals name will be displayed on the cage or enclosure (because otherwise keepers are pestered constantly by the public wanting to know what the animals names are), but more often than not the animals do not have names and the keepers are discouraged from any handling or direct interaction with an individual animal. This leads to many problems with the care and maintenance of many animals, and has in fact led to the death of some animals at well-known zoos (e.g. an elephant at London Zoo in the 1980s). In fact, a couple of zoos have now dropped their zero-handling philosophies (e.g. Chester Zoo) in favour of the handling of some animals. The rationale of which animals should be handled and which not does not seem to have been very clearly defined.

I have only come across one zoo, and that a particularly interesting small private zoo (Twycross), where, although environmental messages are frequently and imaginatively displayed, the central concern is with the individual. The management began the zoo originally, not with ideas of having displays, collections, and zoological gardens, but rather to provide a home for unwanted pet primates. Although the zoo has grown and is apparently in line with the mainline establishment thrust of zoological gardens, the fundamental philosophy is very different and permeates through the general atmosphere and to all working there. The concern is primarily with the individual rather than the species.

Concern with the individual as opposed to the species may result in emotional bonds establishing between animal and handler or keeper. In general in zoological circles such an approach is considered unscientific, and mainline zoos like to be considered primarily scientific establishments. Concern with the individual smacks of pet keeping, empathy, and emotional involvement... although why behavioural science should deny or ignore emotionality is mysterious. Nevertheless, there is now a growing awareness of the importance of individual differences in ethology and the behavioural sciences [131]. Emotional involvement of humans with animals does not necessarily indicate human inadequacy, is not necessarily a substitute for human-human emotional involvement but can be something enriching and important in itself.

Much can be learnt both about the animal and its species, and about oneself and other humans. As a result, changes can be made in human beings attitudes to animals, and their own place in the biosphere by developing and encouraging emotional attachments and studying individuals. In addition, the general public often find this a much easier entrance to general environmental education (note the large number of childrens books about animals) than the perhaps more immediately intellectual interest in species and environmental issues which is usually adopted by zoos. The reason why Virginia Mackenna and Bill Travers founded Zoo Check was because they had become involved with individual lions.

Circuses by their nature emphasise the individual, the training is individually done, and the performances rely on relationships between individual human and animal. Thus they are uniquely placed to educate the public in both individual and species differences and similarities, and those between humans and other animals. At present very little education of this nature is done in the circuses, although many would like to see it (Appendix 3). If circuses are going to continue to exist, then it is important that they take their educational role seriously and develop it.

4) The provision of recreation and entertainment

This is where both zoos and circuses began. Provided the animals do not suffer, and the environment and their survival is not threatened by providing for human recreation and entertainment, there seems little reason why this should be condemned.

Zoos often combine their animal exhibits with the provision of playgrounds, fair grounds, picnic areas, gardens, restaurants, and status architecture, the idea being to draw as many people in as possible. Like everything else in the zoo these are sometimes done well and thoughtfully, and sometimes not. Occasionally further entertainment is provided by the animals giving rides, pulling carts, or giving displays, chimpanzees tea parties or dolphin and whale displays. Here there is a combination of zoo and circus, and they are often very popular. The acceptability or not of such displays from the point of view of the animal has been discussed in Chapter 6.

Similarly the circus, although fundamentally there to entertain and perform with their animals and human acts, often has a menagerie, or small travelling zoo. This attracts people to wander round the encampment during the day, to attend the training sessions (if there are any), and that in turn will encourage them to come to the performance.

Provided the animals acts are appropriate for the animals and designed to make people respect them, and they and the environment do not suffer as a result, there is little reason to condemn travelling menageries and animal performances. One of the arguments used against circuses is that the animals lose dignity by performing and this undermines humans attitudes to them. We have discussed this already on page 129 et seq..

What evidence is there that by providing recreation for humans, zoos and circuses are having a beneficial effect on humans or animals, directly or indirectly? There are obvious advantages, for example they can provide pleasant surroundings where families will go to relax and enjoy themselves away from day to day life. Although such environments are not completely rural, they can introduce the urban dweller, often for the first time, to the real experience of other sentient intelligent beings and other aspects of the natural world, and offer facilities for her to ponder on her ideas, attitudes to and understanding of the living world outside her own.

Often they provide experiences of the live animals, their smells, their presence and size which cannot be gained from television wildlife films. Particularly in circuses and perhaps the childrens zoo, the public can often touch and directly interact with individuals, which is possibly the best education of all, and certainly the most popular. Humans seem to want to do this. They will immediately ask the name of an animal, and then they will want to feed him or her in order to have a direct interaction with the animal. In the circus most of the audience will go out the back after a performance to see the animals close to, perhaps even touch them and interact with them.

These are things that the wild animal, the animal in a safari park and the television film cannot provide. Perhaps the most important way to change humans attitudes to animals is by increasing their familiarity with them, not to admire the animals from a distance as beautiful paintings, but as intelligent beings that love or hate, learn and think, eat and defecate, and in many ways are more similar than different to human beings.

5) To make money, and run an efficient business

Although this is rarely if ever a stated aim of either zoos or circuses, unlike farms who often give their raison detre as money making, nevertheless it usually has to be a central criterion. Certainly zoos, except in some Eastern-bloc cities, are not considered as a service like schools or research institutes which are not expected to make any money or even cover their costs. Some zoos are sponsored in some way or another, by city councils or foundations, but they are usually still expected to cover their running costs from gate fees and other money-making activities.

The majority of zoos, though, are entirely self-financing and they must not only finance their running costs, but any capital improvements or changes that they require. One is constantly reminded by the management that the economics are a key issue in many zoos when suggesting changes or improvements to animal housing or management. Yet some zoos spend very large sums on status buildings which receive much publicity and are often used to enhance national standing, for example the Snowdon Aviary or Hugh Cassons Rhino and Elephant House at London Zoo, the Jungle World at the Bronx and many others.

In urban zoos (usually because of the need to make money by increasing the gate), there is a constant competition for space: people versus the animals. Often the result is that more space is devoted to people for their pathways, toilets, restaurants, play areas, picnic areas and gardens than for the animals housing and runs. This is a difficult problem to resolve, but with good planning and a real commitment to improving the conditions for the animals, it usually can be, and it does not necessitate large expenditures.

The rising land prices, particularly in inner cities, has ensured that many zoos have considerable capital assets. Some have cashed in on some of these assets to buy land outside the city and start wildlife parks, such as London Zoo and San Diego, California. However, one cannot help thinking that if their priorities really were conservation, conservation education and research, that they might do more good for these causes by selling out and giving their money to organisations which exist only to do these things, or otherwise to start their own foundations or conservation centres where the animals can be in their native habitats.

With the exception of the Moscow State Circus, and possibly some other Eastern-bloc circuses, the circuses throughout the world are self-financing and usually they make this quite clear. They are run as businesses: one of the major reasons for running a business, for some animal businesses often the only one, is to make money (e.g. farming).

Recently circuses in Britain have had declining audiences and have had a hard time financially. If money making was their only, or their prime, motive for running circuses, many would have quit. With their considerable capital assets (trucks, tents, animals, and often land for winter quarters) they could successfully have gone into other businesses. However, few of them have and this would seem to be because circus is a unique way of life; the only type of life which many circus people have experienced since they tend to be born and remain in the circus all their lives. In fact, some circuses do run other businesses to help finance the travelling circus in hard times: making and hiring out tents is a favourite one; others run safari parks and animal-training businesses.

Nothing succeeds like success in circus as in other businesses. As a circus begins to become prosperous, the standards go up, the performance improves, the atmosphere becomes positive and this attracts more people. It also allows improvements in, for example, the animal housing and transport facilities, the tent seating, hiring of a band instead of having taped music, and so on. This difference was very obvious when I visited Circus Knie in Switzerland which is considered a very respectable, commendable institution. There is a childrens matinee, but adults attend the evening performance and it is treated rather like going to the opera or ballet.

Only a few zoo directors or keepers (and those of small zoos that they have usually started themselves), say they run the zoo because it is a way of life. As a rule they do it because it is a job which allows them to exercise their particular skills, and they leave their normal house in the suburbs and go to work and come home in the evening to their families in much the same way as the vast majority of people.

On the other hand, the circus proprietors and directors, as a rule, travel with the tented circuses. This is a different way of life. They are nomads and live in trailers or caravans, and apparently have no wish to have houses. Indeed often there are houses at their winter quarters, but in almost all cases the houses are not lived in but are used for storage. When the circus people move to these quarters for their short winter break (December to March) they usually stay in their trailers. Rather than being relieved to be in one place for a time, they often complain after a few weeks and develop itchy feet aching to get back on the road.

When on the road, the circus people live 24 hours a day at the encampment. Then after a short period they take the whole thing down and pack it all into trucks to erect the whole village - or in some cases, township - in another place that night. The logistics, independence, self-reliance, ability to cope with all contingencies, entrepreneurial skills, and sheer hard work are very impressive.

All sorts of people, from ex-criminals to bank managers or lawyers, may join the circus for short periods of time to help in lowly capacities - such as ring boys and grooms. The circus forms its own society and although they must mix easily with people wherever they go, nevertheless the close-knit circus community functions like an extended family and they look after each other. The very young and the very old travel with the circus, and there is always a job that person can do. It is not unusual to find four generations of a family with a travelling circus.

Despite the hard work and often primitive living conditions, this way of life is very attractive to some from outside the circus. Several who have joined the circus said that they feel that at last they belong somewhere. Another attraction is that it is a classless society - ones background and status outside the circus become irrelevant, what matters is your performance within it, and commitment to it: The show must go on. It is possible in a relatively short time to work ones way up from being a tent hand, ring boy or groom, to being an artiste and then to being hired by other circuses, maybe in other lands. There is a constant exchange of artists and acts around the world, and circus people always know, or often are related to, other circus people the other side of the world. Even small British circuses touring around village greens will have some artistes from romantic-sounding places - Morocco, Italy, or wherever; circuses are truly international communities. As a result of these things, and because the circus will often give a chance to a young person who would like to try out his/her own creativity, animal training, or acting abilities, there is a constant recruit of people joining the circuses annually. Not all stay there for life, but a fair percentage do, often by marrying into an old circus family.

Another characteristic is that the circus people live all the time with their animals. The result is familiarity with, and treatment of each animal as an individual. Young animals of many species are often raised in the trailers, and with the exception of a few of the large cats, all the animals are handled daily.

It is more than a sub-culture, it is rather a culture of its own with its own priorities and value.

There is much to admire in circus culture and in this age of increasing uniformity of human culture, there would be much to lose if circuses were to go. If it can be retained, while also allowing the animals to have a high quality of life and suffer minimal distress, then why should circuses be banned or outlawed?

To conclude, there is no insurmountable reason why all of these aims should not be fulfilled for circuses, with the possible exception of breeding endangered species which it might be argued is likely to be more successful in the animals natural habitat. The type of research needs to be examined carefully, with the individual animals interests paramount. This is not always the case in the zoos. It could also be argued that environmental education might be better achieved in different surroundings, and with different modes than displaying exhibits in collections.

There is a very neglected area of education and research in zoos which would make a better argument for zoos, although circuses are probably generally better placed to do this: this is to emphasise the uniqueness, intelligence and abilities of individuals as representatives of species. Their similarities, in terms of emotional response to human beings, and the sophistication of possible communication between humans and other species can be best displayed in training and thoughtful animal performances.

The degree to which these criteria are actually fulfilled varies greatly, as do the priorities which different zoos and circuses give to them.

The zoos are least good at the argument they make most of: breeding endangered species. Although some species have been bred successfully in zoos, for every species bred, zoos over the course of history have contributed to the extinction of another by creating a market for their capture. Indeed the trade in rare and endangered species to exhibit and try to breed continues to exist. The foetal transplants and similar biotechnological advances are open to severe ethical and scientific question in this context and should not be used by zoos to support their existence. The individual animals needs should be considered, as they would if such techniques were to be applied to human beings.

Environmental and ethological field research is being conducted by a few zoos, but zoos may not be the best place to do this. What is happening in only a few zoos is research on optimising the animals environments and fulfilling their physical and behavioural needs within the context of a zoo. Thus there should be no evidence that the animals life within the zoo is of low quality or that the animal is distressed or severely restricted behaviourally. This is an area that requires an inter-disciplinary knowledge and a holistic approach, as well as originality, creativity and practical expertise. The case for the continual existence of zoos would be strengthened infinitely if such research programmes were more frequent and seriously embarked upon, and such work was not left to those outside the zoos to finance.

Although zoos have recently developed interesting environmental educational programmes, nevertheless it has been argued that this can be better done by television and films without the animals having to be confined in artificial environments [35]. Again one feels that their jumping on the environmental bandwagon in justifying themselves might be misplaced, and opens their approach to more criticisms than achievement. It might well be that zoos, as well as circuses, should rather concentrate on giving experiences and education that the television and film cannot do.

Zoos do provide recreational facilities which are often much appreciated by the public. These are nowadays better designed and in keeping with the environmental philosophy. However, one is somewhat suspicious about whether the priorities are right when the zoo is famous for winning prizes for its rose gardens (Chester Zoo, England)! A careful, self-critical eye should be directed at themselves from time to time by the zoo directorate. The environmental impact both locally and globally must be assessed. Using imported timber from equatorial forests in the construction of the save the equatorial forests exhibit is not what most people would consider appropriate (see Chapter 9).

That one of the main aims of zoos and circuses is to make money (however this is spent) is a truism, and it would be silly to deny it. It might well be that the business is not always particularly well run and that a saving in one direction, such as carrying out certain animal management practices which require less labour, could free money to be used in a better way for the animals welfare. Good animal management is not necessarily more expensive. In fact, one of the ways in which improvements in the animals management are being made in the circuses is by such suggestions.

Circuses are now beginning to think about arguments, other than providing recreation and entertainment and making a living, to justify themselves in the publics increasingly critical eye. They are uniquely placed to contribute in many ways, but must do more of this.

Conservation and zoos and circuses

Arguments for the care of the environment tend to get thoroughly muddled up with arguments either for or against zoos in particular. Their relevance is not always clear [e.g. 9; 35]. We will try and make some sense of the arguments here, and their validity, or not as the case may be.

In the last decade or so, zoos have come under attack from animal welfare and environmental organisations, which are not necessarily the same. Many zoos have, as a result, argued that their real value to the world at large is to preserve endangered species. This argument can be assessed on various grounds: whether or not they can and are doing this, whether this is a good thing anyway, and whether there will not be other environmental effects as a result of zoos doing this. There is also the effect on individuals: should individuals be considered as gene-preserving machines or not? There has been much written about all of these points in the last decade [9; 35]. It is not our intention to re-examine all these in depth. Given that the preservation of endangered species is not necessarily a bad thing, how should it be done? Are there other considerations here? The main points which emerge are:

This still leaves many areas for decisions to be made in individual cases, and vague areas (e.g. who is to say what is a similar enough habitat?)

The end result of such thinking will be towards breeding self-sustaining populations of animals in zoos and circuses.

Meanwhile is it acceptable to consider that breeding endangered species is the most worthwhile aim of the zoos? Midgeley [103] argues against what she calls keeping animals on ice. If the animals individual needs and desires are thwarted in order for it to be displayed in a similar way to works of art, or something to be admired from a distance and kept around (despite the fact that we have destroyed their habitat), then this would not be acceptable.

It would seem that if this was the only argument for zoos (and circuses) then they would do much better selling all their real estate (some very valuable stocks) and giving all this money to establish and maintain wildlife conservation areas in the animals countries of origin in their own habitat.

To go to the level of attempting artificial insemination of tigers, involving frequent immobilising, surgery, drug treatment and so on in order to try to keep a particular sub-species going [9] is not really concerned so much with conservation as with experimenting with reproductive physiology.

The origin of zoo and circus animals

One of the important aspects to look at, therefore, is the origin of the animals in zoos and circuses and in particular to find out how many have been wild caught. I have not done this for zoos, but there are good records and it could be done. Figures 23, 25 and 26 show the origin of the animals in circuses dividing them up into those wild caught, zoo bred, circus bred and other origin (such as pets, sale yards, private breeders).

More than half of the carnivores were circus born (54%), 40% came from zoos, and none were wild caught.

The elephants are the most important wild caught group. The majority of the Indian elephants were between 20 and 30 years old, and it is unlikely that more will be imported because of legislative change to prevent it. Young African elephants are still being imported, but these are from populations that are being culled due to human population pressures and environmental demands. It can be argued that their importation is of benefit to the animal as at least they are alive rather than dead, provided the environment they live in thereafter is appropriate, and they show no signs of prolonged distress.

Of the rest of the wild ungulates, 27% were circus born, 5.7% were from zoos, and some unknown in origin.

Relevant to this debate is the number and types of animals fouod in the circuses. Figures 23, 25 and 26 give a list of the 41 species of animals we found in the circuses.

Twenty six (63%) of these species are generally considered to be wild species, the remaining 37% domestic. The numbers and types of animals in circuses is not stable, and this represents the position from winter 1987 to winter 1988. Animal acts are exported and imported frequently, and the animal species represented in the circuses also follow fashions. However there are not a great many animals in circuses anyway - a total of 513, of which 50 were canaries and pigeons, 128 horses, ponies, donkeys and mules, and 43 dogs. A total, therefore, of 292 traditionally wild animals.

The mammals

The figures give the relative representation of the different species. By far the most popular mammalian species were horses and ponies which were present in all circuses (75 horses: 17.7%, and 49 ponies: 11.6%). Dogs (43: 10.2%) were also well represented, although not all circuses had performing dog acts.

The most common of the wild animals were tigers (58: 13.7%) and lions (43: 10.2%). Five circuses had elephants and they represented 8.49o of the mammals in number.

The camelids (camels, llamas, guanacos and alpacas) are also popular circus animals, and together represent 9.1% of the mammals. Zebras were also relatively numerous, and represented 3.7% of the mammals.

The other species were relatively rarely represented with often only one individual present.

There was only one emu, but the other birds - canaries, macaws and pigeons - were in large breeding groups which is why their figures are high. Two circuses had acts with only a few pigeons or macaws.

There were only two snakes in the circuses at the time when the survey was conducted (winter 1987 - winter 1988).

As stated, the total number of animals in all circuses visited was 513, less than in one of the medium sized zoos.

Breeding of animals in the circus

Many consider that the travelling show is not conducive or appropriate to animal breeding. It is not evident that this could never be the case, but it certainly might be more difficult to provide the necessary suitable quarters for maternity and raising the very young. One circus, as well as having a static training ground and a travelling show, also runs its own safari parks where many of the animals are bred.

It is in the winter quarters that much of the breeding and raising of the replacement animals takes place. The circuses record on animal breeding is not at all bad. We can see from Figures 23, 25 and 26 column 5 that they bred 28% of the carnivores, and 13% of the hoofed stock - a total of 41% of their mammals. The snow leopard had a litter of four cubs, and one circus was trying to breed lynx, leopards and puma all of which had bred successfully before. The bears, guanacos, alpacas and zebras have also bred in circuses.

The breeding record for elephants, both in zoos and circuses, is bad but little serious effort has, until recently, been put into it. One Indian elephant was born in a European circus in 1984, but she died in 1988. It is no longer acceptable with the elephant on the endangered species list that so many cows of reproductive age should be in either zoos or circuses and not be breeding. It is of urgent priority that at least the Indian elephants in the circuses should be allowed to breed. There are at least three adult bulls at stud (or who could be) in Britain today. It may not be possible for many reasons to breed all the females in one year, but at least the cows should go to the bull in sequence, and every effort be made to breed and raise as many calves as possible. Every encouragement should be given to their owners.

The inter-relationship of zoo and circus animals

Recently zoos have been over-producing Burchells zebra and these have been bought by several circuses. Over 66% of the zebras in the circuses are of zoo origin. It is particularly silly to find that several zoos will not admit to this trade; indeed they often proclaim that they would not sell their animals to circuses or any travelling menagerie [9]. This implies that the zoos are in some way superior in their animal management to circuses or travelling menagerie. That this will necessarily be the case is not clear either in theory or in practice. In some cases, the reverse might be true.

Fig. 64. A breeding group of elephants in a zoo.

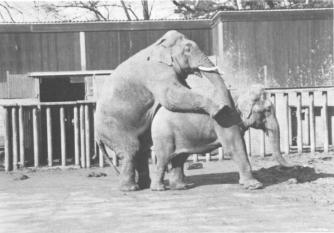

Fig. 65. Mating in elephants, and breeding is quite possible in circuses and zoos.

Fig. 66. A tiger family (mother and cubs in one den, father next door) in a travelling circus. Outside exercise runs with objects to play with and manipulate, and good views, should be provided as well as social contact with humans, such as seen here.

Selling off the zoos surplus to circuses can often offer life to that individual instead of death. It would be possible for the zoos and circuses to work more closely to provide a home and a job for as many animals as possible that are born in the zoos. In fact, this can work particularly well for placing spare zoo-born males who are not required for breeding and the zoo may not be able to keep, but who would be welcome in the circuses who often prefer males.

The ratio of males to females in many species in the circuses is heavily weighted in favour of males (see Figures 23, 25 and 26). The reason for this is that males are often more spectacular, and show themselves off better than females, for example stallions compared to mares. They can be slightly more difficult to handle, and require more individual attention in order to adapt well to the environment than some females. For this reason as well they may be more suitable for the circus where there is a concentration on the individual and they have more professional handlers and trainers than in the zoo.

Conclusions

Thus it can be concluded that provided the animals are kept in an ecologically, ethologically and ethically sound environment, and that the costs and benefits to the individual and the environment at a whole are seriously considered there is no reason why animals should not be kept and bred in captivity.

Although the preservation of endangered species is used, particularly by zoos, as their central raison detre, there are other reasons which make better arguments for the existence of appropriate zoos and circuses. Having said this, though, there is no reason why circuses as well as zoos should not contribute to conservation aims and breeding of endangered species. Circuses can and do breed various endangered species and a relatively high percentage of all their animals. They also can offer a chance to life to animals surfeit to zoo requirements. It would seem that zoos and circuses should work more closely together and make better use of each others knowledge and skills to improve along appropriate lines.

|

Any

non working links, comments or suggestions please contact the webmaster:

johneaston@diddly.co.uk |

|